✿ Review fr✿m last week ✿

Last week we learned about moving from static compositions that create a single fixed frame, to interactive compositions that can respond to mouse input to create kinetic, moving images. In Processing this is often called active mode.

To achieve that we learned some new syntax, mainly,

the setup()

and draw() blocks:

def setup(): # Things here run once, at the start of your program def draw(): # Things here run many times, once per frame

In static mode, your sketches ran once in a split second, and then stopped, frozen forever, but now, in active mode, your sketches unfold in human time. Because of this, you need to ask yourself when commands will be executed: once at the beginning of your sketch, or once per frame? With raster images for example, you want to load them once, at the beginning of your sketch, but you will probably want to draw them every frame. You would do that using the code blocks that you just learned about like this:

def setup():

global img

img = loadImage("some-image.jpg")

def draw():

global img

image(img,0,0)

NOTE: This is the pattern that you should use for working with raster images from now on.

We also saw how to use mouse movement with mouseX

and mouseY.

Last week's lecture notes also talk about pmouseX

and pmouseY. Those special variables will give

you the position of the mouse from the

previous frame. So if you are

curious about that, have a look at the class notes. For

example, here is how you could use those two variables to

calculate the distance the mouse pointer traveled from one

frame to another:

def setup():

size(600,600)

frameRate(4)

def draw():

distance = dist( pmouseX, pmouseY, mouseX, mouseY )

print(distance)

And lastly, we saw how we could use these special variables in

ways that are more flexible and powerful by using

the map() command. This command translate or

"maps" a value or variable proportionally from one range of

numbers to another range. For example, the following code

uses mouseX to position a rectangle, but limits

its movement to a 100 pixel range:

def setup():

size(600,600)

def draw():

rectangleX = map(mouseX, 0,width, 300,400)

rect( rectangleX,300, 50,50 )

The lecture notes from last week show several other examples of this command that you can hopefully use as patterns or templates that you can apply to your own work.

✿ ✿ Making things move and conditionals ✿ ✿

This week we will build on last week in two ways.

First, we will learn how to use conditionals so that instead of the continuous change of mouse movement, you can create movement that is discrete and discontinuous.

Second, we will build on our use of variables and Processing's interactive mode to create things that move on their own, not only as directly controlled by the mouse.

Background

Last week we saw how to make interactive compositions, but they were always moving in continuous, connected ways. Colors that changed as smooth gradients, shapes that moved along with the mouse, or that left smooth trails.

Today we will see how to work with one of the fundamental principles of digital media with is how to work with discontinuity, or on/off relationships. This kind of behavior is often described as discrete. (Not to be confused with "discreet"!)

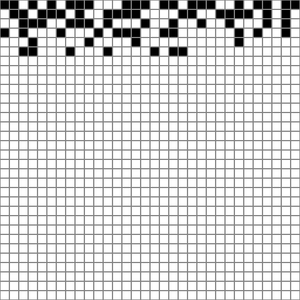

In 1997, the net artist John Simon created a project called Every Icon. This conceptul work enacts a play of combinatorics by starting with the first (top, left) pixel of a 32 by 32 grid, and advances in sequence, creating every possible combination of pixels, or in other works, every possible icon.

This work emphasizes the way that all digital images are created not as smooth strokes, continuous marks, or smooth lines, but rather always as grids of pixels, always turned either on or off.

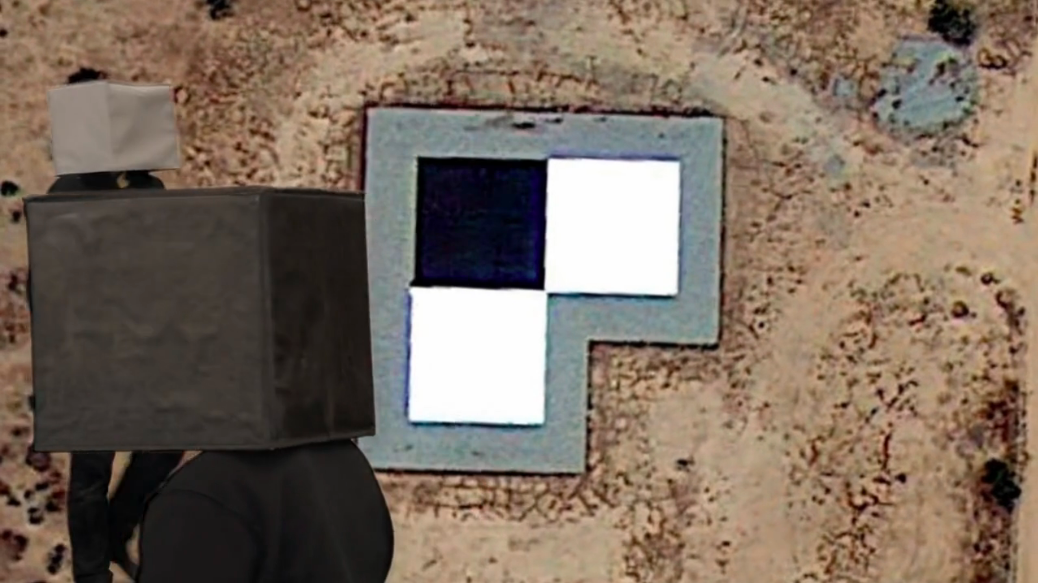

To similar ends but in a more poetic and ironic way, the artist Hito Steyerl, in her documentary How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File, explores (and blurs) the boundary between the analog and digital, between the physical world and the world of digital representations, or in other words, between the smooth and the discrete.

Let's keep all of this in the back of our minds as we explore the logic of discrete on/off structures today and dive in to binary logic.

mousePressed and keyPressed

In addition to mouseX and mouseY,

Processing gives us some other variables that we can use to

create user interaction:

mousePressed tells us if the mouse is currently being pressed, and

keyPressed tells us if the any key is currently being pressed

But what is if? So far, variables have only had numeric values. How can a variable tell us "if" something?

These variables are of a new kind of value. We say that they are a new type, and it is called Boolean.

Just like with the numerical values and variables that we have

been using, Boolean variables can be used

whenever we want to keep track of something with only two

possible values: yes or no, on or off, visible or hidden. Their

value is always only either True

or False:

isDrawing = False # or isDrawing = True def setup(): # setup def draw(): # draw

Notice that I'm writing True and False

as valid Python code. That is because they are actual values

that you can use in your code just like numbers, which in

technical jargon we call literals. So far we

have seen numerical literals like 0, 1, 2, 10,

300, etc, and string literals

like "hello". You can see this

with println():

def setup():

size(600,600)

def draw():

println(mousePressed)

# mouse pressed is a boolean variable !

...but how do we actually use these variables?

Conditionals

Conditionals are ways of asking if something is happening or not, and to allow our code to have different behavior in each case.

Your code can now be more than one simple set of top-down instructions, and can instead have the possibility of doing different things depending on various variables, calculations, and user actions.

A note on pseudocode. (Pronounced, "SOO-doh code".) So far, all the code that I've shown you has been valid Python/Processing syntax. You could copy/paste it into the PDE and it would run. Now we will start talking about a thing called pseudocode. Pseudocode is basically plain English, but with some bits of valid code in it. There are not hard and fast rules about valid pseudocode. Rather, it is a way of writing out an algorithm in English with bits of actual code in it. It is a way to describe an algorithm and work it out, without implementing it yet.

If a question is True: # run some commands

As an example, let's start with this code that draws a circle in the middle of the window:

def setup(): size(600,600) def draw(): background(255) ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

Now, let's draw this circle only if the user is pressing the mouse by adding this new syntax for conditionals:

def setup():

size(600,600)

def draw():

background(255)

if mousePressed:

ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

Some new syntax rules:

You write if followed by

a Boolean variable (or an expression that

evaluates to True or False

— we'll look at these below).

You do not need to put your Boolean

expression in parentheses, but they are

optional. Later on when working with more complicated

logic, you will see examples in which you will need or

want parentheses here.

Notice the indentation.

The if statement

introduces a new

code block, so after your

Boolean expression, you add a colon, and

the next line must be indented. The block continues until

you stop indenting. The block can contain any arbitrary

Python / Processing statements that you wish, and we say

that all of the statements of this block are

inside this if statement.

Most importantly: The code inside

the if statement only gets run if

the Boolean expression evaluates to True.

Think of this as allowing you to ask questions, like, "Is the mouse being pressed?" I recommend reading the above code in pseudocode in the following way:

If the mouse is being pressed, then draw an ellipse.

You can combine questions together using boolean operators.

and, both parts must be True

or, only one part must be True

(either or both is fine)

not, the expression that follows must

be False

Here are some examples:

if mousePressed and keyPressed: ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

If the mouse is being pressed and any key is being pressed, then draw an ellipse.

if mousePressed or keyPressed: ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

If either the mouse is being pressed or any key is being pressed, then draw an ellipse.

if not mousePressed: ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

If the mouse is not being pressed then draw an ellipse.

In addition to the special Boolean

variables mousePressed

and keyPressed, you can also ask questions about

numbers that you are using in your sketch. Consider the

following pseudocode:

If the mouse is on the left half of the screen then draw an ellipse

Let's get more specific:

If the mouse x position is less than 300

then draw an ellipse

And now let's translate that into real Processing code:

def setup():

size(600,600)

def draw():

background(255)

if mouseX < 300:

ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

The full set of yes/no questions that you can ask about numbers are:

< less than

> greater than

== equal to

<= less than or equal

>= greater than or equal

!= not equal to (This is equivalent to

using == and preceding the entire expression

with not)

And just as with mousePressed

and keyPressed, you can combine these together

with boolean operators to ask more complicated

questions. Let's start with some basic pseudocode:

If the mouse is being pressed in the left half of the window then draw an ellipse

Get more specific:

If the mouse x position is less than 300 andthe mouse is being pressed then draw an ellipse

And finally translate that into valid Processing syntax:

def setup():

size(600,600)

def draw():

background(255)

if ( mouseX < 300 and mousePressed ):

ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

Try moving the mouse to both sides of the window with and without clicking to see exactly what's happening.

In the above examples, if the Boolean expression

is False, nothing happens. In other words, if the

mouse is not being pressed (to take one example from above)

then the code has done nothing. Well let's add another

shape:

def setup(): size(600,600) # Note that I'm adding the following two lines # so that we can see both shapes together, # and to draw both shapes at the same x,y noFill() rectMode(CENTER) def draw(): background(255) if mousePressed: ellipse(300,300, 50,50) rect(300,300, 50,50)

Note the indendation. The rect() command is not

inside the if statement, so it gets run

always. The blank line is not required and I added it only for

clarity. As you can see, the if statement

applies only to the cirlce, and the square is being drawn

always. What if we only want the square to be

drawn instead of the circle, in an "either / or"

fashion. Well you could use the logical not operator

and write two conditionals like this:

def setup():

size(600,600)

noFill()

rectMode(CENTER)

def draw():

background(255)

if mousePressed:

ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

if not mousePressed:

rect(300,300, 50,50)

But, it turns out that this is such a common thing to do in

programming that there is a special syntax for it: else

You write this in Python like this:

def setup():

size(600,600)

noFill()

rectMode(CENTER)

def draw():

background(255)

if mousePressed:

ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

else:

rect(300,300, 50,50)

I recommend reading that in pseudocode like this:

If the mouse is being pressed then draw an ellipse Otherwise, if is not being pressed, then draw a rectangle

else is kind of like saying "otherwise" in

English. It is the thing that happens if none of the conditions

are met.

A note on syntax:

if starts a new conditional

block. And any time you see if, it is not

related to past conditionals. So the above example could

have looked like this and would have still been valid:

if mousePressed:

ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

# lots of other commands here ...

if not mousePressed:

rect(300,300, 50,50)

However, else must come immediately

after an if block, and it is logically

connected to that if statement. So this is

invalid:

def setup():

size(600,600)

noFill()

rectMode(CENTER)

def draw():

background(255)

if mousePressed:

ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

background(220) # this is invalid code!

else:

rect(300,300, 50,50)

And instead must be written like this:

def setup():

size(600,600)

noFill()

rectMode(CENTER)

def draw():

background(255)

if mousePressed:

ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

background(220)

else:

rect(300,300, 50,50)

in which case the logic of the else must be

understood in terms of the preceding if. In

other words, it means "do something if the mouse is not

being pressed."

Let's work on another example starting with the following pseudocode:

If the mouse is on the left of the screen then draw a circle Otherwise, if it is in the middle of the screen then draw a square Otherwise, if it is on the right of the screen then draw a triangle

In this case, to get more specific, we could say this in two different ways that are both logically equivalent:

If mouseX < 200 then draw a circle If mouseX >= 200 and mouseX < 400 then draw a square If mouseX >= 400 then draw a triangle

If mouseX < 200 then draw a circle Otherwise, if mouseX < 400 then draw a square Otherwise draw a triangle

Here on the top, we are being explicit about each logical

case. While in the bottom example, we are using this "otherwise"

idea to say: "if mouseX is less than 200, then

draw a circle, otherwise (if it is not less than

200) if it is less than 400, then draw a square."

This idea of "otherwise if" has its own syntax, and that

is elif. We would write the above

example in the following way:

def setup():

size(600,600)

noFill()

rectMode(CENTER)

def draw():

background(255)

if mouseX < 200:

ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

elif mouseX < 400:

rect(300,300, 50,50)

else:

triangle( 300,275, 325,325, 275,325)

This new syntax (elif) uses the fact that the

first part of the conditional (mouseX < 200)

is False, and then adds another question. So it's

like saying "Otherwise, since mouseX

is greater than 200, if it is less than 400, then

draw a square." And in this example, the

final else now says "Otherwise,

since mouseX is greater than 400, then draw

triangle."

Note that the order is important here. For example, think about what would happen if we switched the order of the first two conditionals. If you wrote the following:

if mouseX < 400: ellipse(300,300, 50,50) elif mouseX < 200: rect(300,300, 50,50) else: triangle( 300,275, 325,325, 275,325)

The square would never get drawn. Why? What would make the

first if statement False?

If mouseX is greater than or equal to 400. But if

this is the case, it could never be less than 200.

If elif seems confusing to you, that's

OK. It is confusing. Even expert programmers get

tripped up about these kinds of logical statements all the

time, and they are often the source of time-consuming and

expensive bugs. Fortunately, you can write this example in a

way that is more clear and readable, and that is also

logically equivalent — based on the left-side pseudocode

above, like this:

def setup():

size(600,600)

noFill()

rectMode(CENTER)

def draw():

background(255)

if mouseX < 200:

ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

if mouseX >= 200 and mouseX < 400:

rect(300,300, 50,50)

if mouseX >= 400:

triangle( 300,275, 325,325, 275,325)

This example is totally clear and explicit about each quesiton that you are asking, and is probably the easiest and most understandable way to implement this.

As a final example, let's stitch together several Boolean variables to ask a slightly more complicated question. Let's start again with some pseudocode:

Draw a small square If the mouse is inside this square then draw a circle

Start with the basics:

def setup(): size(600,600) noFill() rectMode(CENTER) def draw(): background(255) rect(300,300, 50,50)

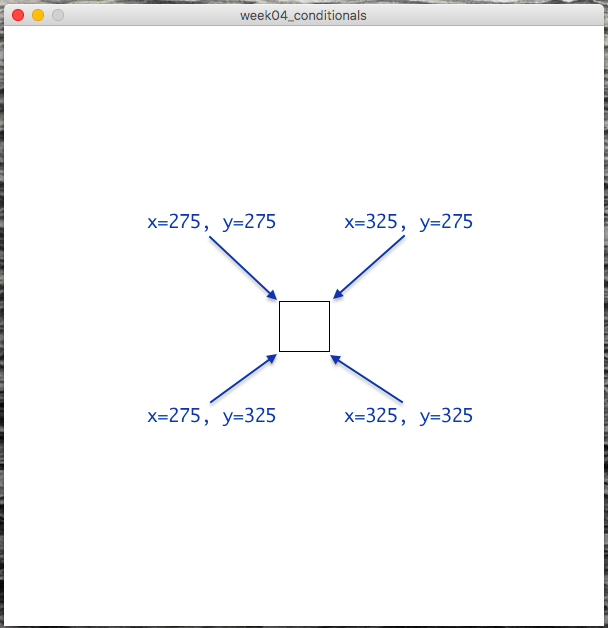

Now before we try to implement the conditional, let's diagram what's going on here:

With these coordinates in mind, let's refine our pseudocode:

Draw a small square If mouseX is greater than 275 and less than 325, and mouseY is greater than 275 and less than 325, then draw a circle

If that's not totally clear, pause for a second and think through the logic of those comparisons to see how that pseudocode describes a check that the mouse is inside the above box.

Moving forward from there, we can now implement a conditional for this description:

def setup(): size(600,600) noFill() rectMode(CENTER) def draw(): background(255) rect(300,300, 50,50) if mouseX > 275 and mouseX < 325 and mouseY > 275 and mouseY < 325: ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

Note that you must write mouseX

twice. In other words, Python does not allow you to

say something like this:

275 < mouseX < 325 # INVALID! Sorry :(

You must write it out as:

mouseX > 275 and mouseX < 325

In other words, our Boolean comparison operators are binary operators, meaning that they only take two arguments.

If you'd like, if it is more clear to you, you could write it like this:

275 < mouseX && mouseX < 325

which is equivalent (note the change from >

to <). Personally I find this more confusing,

but it may look nicer to your eye.

✿ ✿ Keyboard interaction ✿ ✿

So far we've seen how you can use the special

Processing variable keyPressed to let the user

press any key to trigger a conditional action. But this only

tells us if any key is being pressed or not. What

if we want to get more specific and create code that

responds to specific keys?

Fortunately, Processing offers us another special variable

just for this purpose: key.

(Processing

reference. That says "example is broken", but it actually

seems to work OK for me. Maybe there is something I'm

missing.)

With this variable, we are now working with a

variable type that I have mentioned before

called a string: a bit of text surrounded in

single or double quotes. For

example: 'a'

or "b". You can read more

about strings in the Processing

reference, or in the Python reference.

Like everything in Python and Processing, strings are case-sensitive, so:

println('a' == 'a') # would print True, but

println('A' == 'a') # would print false.

Let's add to our example above:

def setup():

size(600,600)

def draw():

background(255)

if keyPressed:

if key == 'e':

ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

Note that I have added a new if

statement inside the previous if

statement. Programmers would call this a

nested if statement, because one is

inside the block of another. It might look complicated, but

hopefully if you think carefully about the logic, it is really

simple. Let's think about it with pseudocode:

If any key is being pressed,

if that key is a lowercase 'e'

then draw an ellipse.

Now where this gets tricky is that there are multiple ways to write this same logic. These ways are all valid, and you can use whichever is more clear and readable for you.

In reading that pseudocode, you might have gotten the impression that I could also have written it like this:

If any key is being pressed, and that key is a lowercase 'e' then draw an ellipse.

and that would make perfect sense. They are logically equivalent. In fact, I could implement that pseudocode in Processing syntax, and it would also work perfectly well:

def setup():

size(600,600)

def draw():

background(255)

if keyPressed and key == 'e':

ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

Use whichever form makes more sense to you and is easier for

you to translate back-and-forth from your natural langauge to

Processing syntax. The important thing to understand is

that nesting if statements is

kind of like and in that both conditional parts

must be True.

Now let's expand on that example and see if you prefer one method or the other. What if we want to add a second key command to draw a square?

def setup(): size(600,600) rectMode(CENTER) # Adding this back for clarity def draw(): background(255) if keyPressed and key == 'e': ellipse(300,300, 50,50) if keyPressed and key == 'r': rect(300,300, 50,50)

Adding more key commands would simply repeat that pattern. And

maybe now you can see here why writing it this way for many

key commands might be a little bit annoying. You have to add

that keyPressed and check every time. Programmers

usually hate redundancy like this and prefer to write things

only once if possible, as it makes code less prone to errors.

Let's change it back to the previous style. Making a change like this is called refactoring. This is a fancy word that programmers like to use that just means re-writing code in a way that is equivalent and usually clearer or more efficient. So let's refactor this example:

def setup():

size(600,600)

rectMode(CENTER)

def draw():

background(255)

if keyPressed:

if key == 'e':

ellipse(300,300, 50,50)

if key == 'r':

rect(300,300, 50,50)

With this style, you are only checking that they key is

pressed once, and if that is True, you have a

series of nested if statements

that then check which character was pressed.

✿ ✿ Events ✿ ✿

In addition to these conditionals

using keyPressed and key, there is

even an important third way of handling keyboard

interaction. Try running the following code and make very

quick key presses:

def setup():

size(600, 600)

frameRate(60)

def draw():

if keyPressed:

ellipse( random(0,width),random(0,height), 50,50 )

My goal was to draw a single circle at a random location each

time a key is pressed. But one key press will likely draw many

circles. That's because the code is responding to a

single key press more than once. Because the frame rate is

going fast relative to human reflexes, it appears that the

user has pressed the key on multiple frame renderings, or in

other words, during multiple executions of

the draw() block.

Another problematic example would be if you slow down

the framerate:

def setup():

size(600, 600)

frameRate(1)

def draw():

background(255)

if keyPressed:

ellipse(300, 300, 50, 50)

This is an exagerated example, but it shows that when you are

only checking for key presses inside the draw()

block, it is possible that you may not respond to all of

them. By pressing keys more quickly than the frame rate

refreshes, you are causing Processing to "miss" your

action. When the frame is being rendered, you are not pressing

the key, you are essentially pressing the key between

frames.

These may be behaviors that you want. But if not, there is another option.

A new code block:

def keyPressed(): # commands in here

This special block is triggered exactly once, every single time a key is pressed. That means that you don't have to worry about it not being called, and you don't have to worry about it being called more than once.

Also, inside this new block (which must always be global, outside all

other blocks), you do not need to check

if keyPressed is True. You know that

your code is responding to one single key press.

This style of interactive programming is called event handling because your code is handling, or responding to, an event that the user triggers. This is an important part of any game development or user interface coding.

For example:

def setup():

size(600,600)

rectMode(CENTER)

def draw():

pass

def keyPressed():

ellipse( random(0,width),random(0,height), 50,50 )

Sidenote: There is a similar pattern here for the

mouse. The mousePressed() block is also valid syntax

and would be used in a similar way:

def setup():

size(600,600)

rectMode(CENTER)

def draw():

pass

def mousePressed():

ellipse( 300,300, 50,50 )

✿ ✿ Making things m✿ve

Changing topics, let's look at how we can make things move on

their own, instead of only moving in response

to mouseX and mouseY, as well as

mouse and key presses.

This is not a complicated topic and only brings together

several things we've already seen, namely: variables,

arithmetic, and frameRate.

Let's begin with the simple example that we've been starting with:

def setup(): size(600,600) stroke(50,50,150) fill(200,200,255) def draw(): background(255) ellipse( 300,300, 50,50)

Now if we want that circle to move side to side, what do we need to add? We want it's position to change and to "vary" ... so we'll add a variable:

circleX = 300 def setup(): size(600,600) stroke(50,50,150) fill(200,200,255) def draw(): background(255) ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50)

Just by itself, this change isn't going to make the circle

move. How could we do that? What we've seen so far would be to

use something like mouseX. So

we could maybe try to modify draw() like this:

def draw():

background(255)

global circleX

circleX = mouseX

ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50)

But what if we want the position of the circle to change "on its own"?

Using pieces that you've already seen, all we'd need to do is

modify the value of the variable inside draw() so

that it changes a little bit each frame. Like this:

circleX = 300 def setup(): size(600,600) stroke(50,50,150) fill(200,200,255) def draw(): background(255) ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50) global circleX circleX = circleX + 1

If that new line is confusing for you to understand, try writing it this way, which is equivalent, and maybe a little more clear:

def draw(): background(255) ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50) temp = circleX + 1 circleX = temp

That might clarify what may to you look like circular logic of assigning that variable to itself.

But! The circle disappears! How can we make it come back? Let's make it so that if the circle moves off to the right, we have it re-appear at the left. To do this, let's think through some pseudocode:

Draw a circle at location circleX Increment the value of circleX by 1 If the circle goes off the window to the right then redraw the circle on the left.

Or, getting more specific:

Draw a circle at location circleX Increment the value of circleX by 1 If the circleX > width then circleX = 0

Now it should be pretty easy to translate this into valid Processing syntax:

circleX = 300

def setup():

size(600,600)

stroke(50,50,150)

fill(200,200,255)

def draw():

background(255)

ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50)

global circleX

circleX = circleX + 1

if circleX > width:

circleX = 0

Nice! I'm sure with a little adjusting, you can modify that so

that we let the circle completely disappear, and then re-appear

smoothly. (Hint: you can set circleX to a

negative value.)

Let's get a little more complicated. What if we don't want the circle to re-appear on the other side, but rather to "bounce" off the wall of the window? Now, instead of only moving to the right, sometimes we'll want the shape to move to the left. In other words, we want the direction of the circle to change. And when we want something to change, what do we need?

A variable.

So let's add a new variable for the direction of the circle:

circleX = 300 circleDirection = 1 def setup(): size(600,600) stroke(50,50,150) fill(200,200,255) def draw(): background(255) ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50) global circleX circleX = circleX + circleDirection if circleX > width: circleX = 0

So far nothing has changed. I've merely swapped in a variable for a hard-coded value. But now, instead of changing the position of the circle when it hits the wall, I want to change the direction. Like this:

circleX = 300 circleDirection = 1 def setup(): size(600,600) stroke(50,50,150) fill(200,200,255) def draw(): background(255) ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50) global circleX global circleDirection circleX = circleX + circleDirection if circleX > width: circleDirection = -1

Great. But now it disappears off the left side. How do we fix this? Do we need a new variable? To answer that, ask yourself: is anything new is changing? No, nothing new is changing, so we don't need a new variable. But we want to change when and how that variable changes. In order to do that, there is another question that we want to ask and respond to. Let's work through the pseudocode:

Draw a circle at location circleX Increment the value of circleX by 1 If the circleX > width then change the increment to -1

And how do we want to modify this?

Draw a circle at location circleX

Increment the value of circleX by 1

If the circleX > width

then change the increment to -1

If the circleX < 0

then change the increment to 1

Looks like we need another conditional. Let's add that:

circleX = 300

circleDirection = 1

def setup():

size(600,600)

stroke(50,50,150)

fill(200,200,255)

def draw():

background(255)

ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50)

global circleX

global circleDirection

circleX = circleX + circleDirection

if circleX > width:

circleDirection = -1

if circleX < 0:

circleDirection = 1

Let's add one more thing. Let's allow the user to

also change the circle direction by pressing some

keys. Let's use 'j' for left and 'l' for right. All we

need to add is the keyPressed() block and two

conditionals:

circleX = 300

circleDirection = 1

def setup():

size(600,600)

stroke(50,50,150)

fill(200,200,255)

def draw():

background(255)

ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50)

global circleX

global circleDirection

circleX = circleX + circleDirection

if circleX > width:

circleDirection = -1

if circleX < 0:

circleDirection = 1

def keyPressed():

# i need one more line of code here in order for this to work, do you know what it is?

if key == 'j':

circleDirection = -1

if key == 'l':

circleDirection = 1

And now, believe it or not, you have all the basic pieces to implement a game like Pong. To be clear, Pong combines many of these elements in a way that may still appear complex, but you should be able to look at this code and have some understanding of what is going on. Take a look:

"""

Basic pong

by Rory Solomon

"""

ballX = 300

ballY = 300

ballXDirection = 3

ballYDirection = 3

paddle1Y = 250

paddle2Y = 250

def setup ():

size(600, 600)

noStroke()

fill(255)

rectMode(CENTER)

def draw():

global ballX, ballY, paddle1Y, paddle2Y, ballXDirection, ballYDirection

background(0)

# draw ball and paddles

ellipse( ballX, ballY, 10, 10)

rect(20, paddle1Y, 10, 50)

rect(540, paddle2Y, 10, 50)

# move paddles

if keyPressed :

if key == 'q' :

paddle1Y = paddle1Y - 5

if key == 'z' :

paddle1Y = paddle1Y + 5

if key == 'i' :

paddle2Y = paddle2Y - 5

if key == 'm' :

paddle2Y = paddle2Y + 5

# check ceiling and floor collision

if ballY <= 0 :

ballYDirection = 3

if ballY >= 600 :

ballYDirection = -3

# check paddle collision

if ballY >= paddle1Y and ballY <= paddle1Y + 50 and ballX <= 20 :

ballXDirection = 1

if ballY >= paddle2Y and ballY <= paddle2Y + 50 and ballX >= 540 :

ballXDirection = -1

# update ball position

ballX = ballX + ballXDirection

ballY = ballY + ballYDirection

Maybe try messing around with that a little bit this week as you work on the homework.